15 Feb 2015 Francesca Woodman’s Fashion

Francesca Woodman: Melancholy Fashion

In February, I visited Francesca Woodman’s show I’m Trying My Hand at Fashion (Marian Goodman Gallery, 24 W 57th, NYC), and have some thoughts, analytical and personal, on the show. Many of the photographs at Marian Goodman for this exhibit are shown for the first time, most were made in the late 70s, and in 1980, many in New York City, a few in Providence, RI, and one in Italy. So, trying her hand at fashion was something Woodman tried several times, and not in one discrete moment, though it seems that after graduation, in New York City, she apparently hoped that she could become a successful fashion photographer, at a time when that seemed a more realistic route than becoming a fine arts photographer. One must recall that for this idea—of using fashion photography to support one’s fine art’s work—Woodman saw successful precedents, Deborah Turbeville of course, but also Diane Arbus cut her teeth as a fashion photographer, and as Christopher Anderson’s dual (or triple) career shows, fashion photography remains a viable way of earning a living while also creating powerful fine arts photographic work.

There are 29 images in this exhibit, I’m Trying my Hand at Fashion, 22 of which were taken in New York City in 1979 and 1980, one of which was taken in Rome, and the remaining six in Providence, RI when Woodman was still as student at RISD. The title is taken from a caption of a photograph; it is not a title that Francesca Woodman applied to this group of photographs. Indeed, given the scattered times and places where fashion photographs were taken, Woodman apparently tried her hand at fashion here and there several times, with increasing interest and intensity in New York City in the year and a half before her death. How can we connect these tiny and in many cases brilliant fashion images with Woodman’s experiements with diazotype, in approximately the same era?

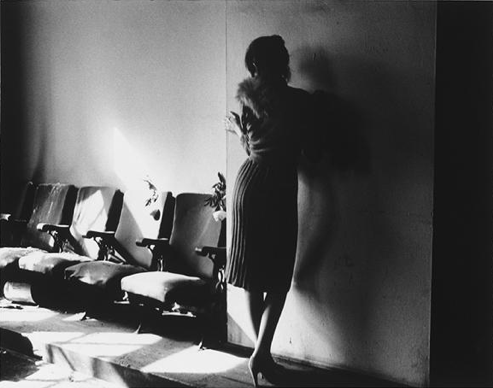

An ontological instability is presented in the images, walls flaking paint, detritus on the floors, and the photographs seem to move into another almost but never quite seen domain, where something very real is grounded, but always withheld; there is something powerful happening in the ‘blind field’ of the photographs, as if someone were moving away from the image, drawing you to look and follow them. The images draw desire in this way, the pale pink and green of the late 1970s room pictured in a small group of images is incredibly nostalgic for me, and also haunting because it’s so cheerful but the women are always displaced, pushed to the edge of the frame, climbing on walls. The whole fragility of the body and its turn in time and space is always eloquent in Woodman’s photographs, articulated by the body parlayed to shadow and corner. Francesca Woodman is very good at finding corners, sharp corners that seem to retreat more quickly from the viewer than ordinary corners– also, sharp chairs, old chairs, fragile chairs that indicate unreliable domicile, and unstable harbor for the body.

An image where Francesca poses herself inside two squares of light uses its peculiarly pointed chair (that looks impossible to sit in, and also shows up in the widely circulated image of Francesca and her father George) to make the viewer aware of the frail and steep construct of rooms and light. Here, the look on her face is so poignant; it’s not at all fashionable, it’s too emotive, but that’s what makes the photograph compelling, as if an accident were caught on its hinge. Woodman’s images do not plan our response to them; with a kind of pure talent, Woodman controls the image but never the audience.

The idea of trying her hand at fashion is transparent: Woodman is sincerely approaching the trope of the fashion photographs. And yet Francesca Woodman’s fashion photographs, some of them captioned with comments that reveal a deep ambivalence about the project (captions such as “this one is more fashion than the other”), are too immersed in querying the terms of the visual to be fashionable; and despite gestures toward Turbeville-like insouciance and visual non-sequitur, Woodman’s images never attain the flat sleek vacuity of fashion. Instead, the images are marked by a sense of texture and gesture that make them move toward the viewer in a disturbing way that is at odds with fashion images’ glissade.

One has to grapple with Woodman’s images in a way that fashion photographs do not usually demand grappling. There is a grist, a traction to her work, textured, visceral, a pull geometric, chiaroscuric, emotive. Woodman’s fashion photographs so often find their way into corners, that a force of the photographs is this sense that one is being pulled into spaces where vertigo reigns. In her photographs, there is an unsettling power that resists the shiny capitalist world of fashion; the images are often startling, sometimes gorgeous, but not sexy in a marketable way. I can see why she did not become a successful fashion photographer; still she improved her art by practicing taking fashion photographs, and some of the fashion photographs stand as works of fine art, now. Trying her hand is the apposite term of the phrase, trying her hand, for Woodman’s work is very much of the juncture between hand and eye, between sight and essay, between possibility and remembrance. She tries her hand, deftly, dexterously,

Woodman, in her fashion photographs, does not dispense with the ruined interiors that she uses in her fine arts photographs and so the echo and texture of ruin haunts the emblems of fashion she puts forward—the broken dilapidated interiors and hyper-maquillaged women— in a way that ravels fashion’s premise of surface without depth. Woodman’s photographs, instead, irresistibly suggest depth—something moves beneath these tiny photographic spaces (I say tiny because on the wall the images are shockingly small); the images often carry a mystical distance, pulling us toward them as if seeking an answer to an ambiguously formulated question. And this pull is not the norm for fashion photographs that instead need to both goad and assuage a viewer. Woodman’s images neither goad us nor assuage.

In a group of nineteen-seventies inflected color images, the pale green and pink suggest femininity, against which backdrop Woodman, in a skirt to match the walls, looks curvy and ultra-femme in high heels. She catches herself taking the photograph in a large mirror, setting off a cascade of framing effects that cause the audience to think of anything but fashion—instead, we see frames, door frame, mirror frame, articulated moulding, and of course the camera itself is articulated in this image, held in the upper center of the frame. The obsequiousness of fashion just isn’t here. Through her multiply echoing camera, Woodman commands space in this image, commands refracted space through mirror, through multiple frames, with the camera at the helm. And so a mis en abyme of watching is established that jars the viewer rather than soothes, as would be fashion’s wont. Looking at this image we are arrested. The image ruptures the illusion of the photograph, what Barthes calls its “invisibility,” and yet the photograph also pulls into it. Looking at this image, we are looking in the mirror and looking into the room and also cast back by the mirror, pushed out of the room by this doppelganger for photography, the mirror. The fashion garment is rendered by analogy as a subjective turn of loss; for its color is almost that of the walls, and the walls caught in the echo of the mirror and camera, camera and mirror, shape frames that cast up the uncanniness of the architectonic, bending attention away from the consumable object pictured, the lovely dress.

This image structures a regression of space, through the mirror and the frames of the doors and window, and also a shifting or displaced chain of signifiers in that the photographer’s face is replaced by her camera. Instead of seeing Woodman’s face, where we would see a face, we see a camera. Her gaze has become the photographic absolute. We cannot see her because she is ceding herself to the photographic absolute, that does not take away her gaze but extends it. The camera extends her gaze in time—the image, in its exponential replication of seen space, is continued into time indefinitely. Whomever looks at the photograph, or at the photograph’s copy, participates in this extension of Woodman’s gaze, the trope of the mirror extended. So also, the photographer’s gaze is extended in time by the trope of the camera replacing the photographer’s face, its lens her eyes. The gaze is extended in space in that the mirror both deflects and multiplies the gaze of the camera, doubling and shifting the gaze of the observer who is at once melded with Woodman and her camera, and pushed to the other side of the looking glass from Woodman and her camera. As Winnicott wrote, an artist is someone who both longs to hide and to be understood. In the above image, Woodman obscures herself (which is not the same as erasing herself) so that the queer geometric and time/space coordinates of her image are revealed. And all in the haunting melancholic pale swimming pool green and baby doll pink of the late 1970s, the last era of lead paint in America.

In pointing out ways that Woodman’s handmade fashion images differ from the typical Vogue shot, I certainly don’t mean that fashion cannot do some edgy turns. But the goal for fashion photography is to suggest just enough mystery to make the audience want to be the model, or buy what she wears. Woodman’s fashion photographs instead make us uncomfortable in our skin, aware of the fragile and all-encompassing terms of space/time, and embodied gazing. Her photographs make us think — about images, replication of forms, about geometry, space, light, about mortal time and dereliction, and about cameras as “clocks for seeing.”

I mentioned that the exhibit at Marian Goodman calls up nostalgia, and I say this because these fashion images, more so than Woodman’s fine arts images, do evoke a specific time, late 70s, 1980, and perhaps do bespeak a panic that is absent in much else of her work; one feels, here, that she made these photographs seeking something and that she didn’t get it—didn’t get a job as a fashion photographer—and one cannot help feeling the pain of that. The photograph showing Woodman’s face surrounded by fur on fur on fur may be an allusion to Surrealism, but above all else it is a description of poignancy, a severing of the terms of embodiment, a punctum of panic. By contrast, photographs from RISD and Rome bespeak deep pleasure and a profound sense of personal and aesthetic power, a young woman in the ecstasy of her art. But the melancholy of these fashion images also for me derives from my own history, in that on seeing the exhibit at Marian Goodman I remember the Woodman’s exhibit at Marian Goodman, in 2004, Woodman’s first exhibit at that gallery. I brought my toddler with me, carrying him while he slept and I looked at the images. That child has now begun Middle School. And, as well, having earlier published one book on Francesca Woodman, Francesca Woodman and the Kantian Sublime (Ashgate 2010), I have now completed a second book on Woodman, called Francesca Woodman’s Dark Gaze, which will be published later in this year of 2015. So, I feel I might be closing this decade of intense focus on her, and that is melancholy for me. Especially I note that my interest has been fueled by the almost constant revelation of new images in the past decade. And I wonder (worry?) that these fashion photographs may represent the last batch of new images. But I do not know. Maybe there are more waiting. One hopes so.

So my February visit to the gallery is attended by this triple sense of personal melancholy —Woodman’s fashion images that more clearly than her other works have a look of being very much made at the end of the 70s, the decade of my infancy, combined with my sense that this may be the end of the stretch of time in which I immerse myself in this work of Francesca Woodman, that has been so powerful for my life, and also a fear that possibly—though I do not know—these fashion images represent the beginning of the end of new Woodman images coming to light. And with that fear of reaching the end of her oeuvre one is reminded what a shame it is that she is not still around to create new work; she would still be in her fifties, now, had she survived. The gallery lay out of the images is clear, crisp, and it does not get in the way of the photographs, all vintage silver prints. The overall sense of weird power, evocation, of the images calling to audience is strong, even despite the melancholy of some images.

An image that seems relatively far removed from fashion, though it does feature a gorgeous velvety dress, was possibly the most powerful of the show. I will close with a discussion of this image. A sense of homelessness pervades all of Woodman’s photography, that is, a feeling of vertigo in built space, a sense of occupying built space transiently, and at some risk. But this photograph, shown below, in particular conveys a sense of unsteadiness because the walls look like they are on fire and the model kneels toward a wall that, by inference, one might assume is also on fire. Due to the low ‘ceiling’ of the photograph it is as if the model kneels in a box where the walls are on fire and yet she stays calm and just reaches to touch the wall. A materiality of instability is figured in this image, even as it is impossible to decipher if candles were used to produce the effect of fire, or, if a pattern of paint produced the look of flames. Regardless, in the frame of the photograph the image is of a wall on fire, and a woman whose face cannot be seen in the frame is kneeling at the edge of this fire. The blind field of the image is spectacular: we are drawn toward the place where the woman is looking because we cannot see her face but only that she is kneeling and there is a wall on fire beside her. The ontological instability is framed as fire and in this photograph the space beyond the frame evokes extreme vertigo—is the space beyond the frame stable, or is it already ashes? The woman kneeling, whose face we cannot see, marks the boundary, she handles the boundary for us, as our proxy in this liminal zone of fire, she is our fire-wall, and so the sacrificial figure veers from fashion which poses but does not go through with sacrifice. By contrast, Woodman’s image visually goes all the way through—here the wall is burning and the woman is kneeling in the one still dark place that the fire permits. It is this magnetic finding of corners in desperate places that marks Woodman’s work apart from the generic trappings by which it could be read.

The photograph appears uncannily to be on fire. The woman is touching the wall, gently, delicately as if seeking possibly a way out from the box of walls on fire or also perhaps as if just to know better the strange substance of the wall, its immaterial fire. The photograph does not so much display the beautiful dress as make us question how the velvet cloth is like fire, and how clothes are like fire, an unsettling comparison to be sure. This image where it looks like the wall is on fire, and a woman who seems almost to be praying kneels, stops short of over-determination: we see the wall is fragile, the body knelt, the low-sky frame of the image oneiric. Here, as in most of the interior photographs, Woodman’s skill with corners is powerful; she makes the corners look sharper and slightly skewed, angling the shot closer to the wall than one would usually stand. That Woodman experimented with placement of her camera is clear from the images; also her father, George Woodman, recalls that, in such experimentality, Francesca once positioned her camera through a hole in the ceiling, in order to get an extraordinary and uncanny angle for her shots. Uncanny that even as Woodman failed at professional fashion she succeeded in creating images, however rough in places, that open themselves in the field of thought, as if through an unseen hole in the image. Woodman’s fashion photographs are often formally masterful and, as I’ve argued elsewhere, theory-producing images. The melancholic turn of these images, though, is surely also secured by what one knows of her fate: that her hope of making a success in fashion didn’t pan out. And so this sense of thwarted desire haunts the images. She wanted to make the things of this world work, wanted success and maybe even the ease success brings; early death was never her desired telos but that which happened to catch her.

- A version of this passage appears in Francesca Woodman’s Dark Gaze. (All rights reserved).