04 May 2014 Rebecca Belmore: the Photograph’s Wound

Rebecca Belmore and the Photograph of the Wound

Barthes argues that the photograph, if it has power, wounds us, shooting a puncturing arrow into our psyches—very much like Cupid, only this Cupid is one of memory and mourning rather than desire. And yet memory, mourning, and desire are never so far apart, as Barthes’s lover’s discourse on photography, Camera Lucida, demonstrates. For Barthes, a photograph’s ‘punctum’ is the force that wounds the viewer, and can never be planned or planted by the photographer. And yet Barthes, in Camera Lucida, claims as the ultimately wounding image a snapshot, of his mother as a child, made by a peripatetic journeyman photographer, an image that Barthes understands would lack power if seen by most of his readers but has great power to him, because it shows him his mother as she truly was, or so he argues. Thus, the idea that inheritance, family stock, and wounding reach a high water mark in photography can be claimed as the central thesis of Camera Lucida. What if one’s inheritance, one’s stake in the family stock, is itself a site of cultural wounding? What if one is part of a group of people, the Indigenous people of North America, who have survived near genocide? What photograph, in that case, could capture the truth of one’s stock, the wound of one’s wound? Not, surely, the unjust images of Native Americans captured for purposes of study and preserved in Natural History collections of museums.

Instead, the work of First Nation artist Rebecca Belmore shows the wound as the place for the photograph and the photograph the place for the wound by staging, in painfully careful tableaux, the mother as wound, the female body as that which bears some scar that the photograph both seals and reveals. Looking at Belmore’s “Fringe” and “State of Grace” I want to talk a little more about how the photograph and the wound—and the capacity to wound as it relates to the pain of seeing – are connected. Belmore’s photographs “Fringe” and “State of Grace” are the opposite of casual snap shot images. They are legible as highly staged images, the scenes surrounding the photographed women stripped back so that nothing is visible except the proscenium effect of the lighting. No possible ‘accidental’ trace, these images purposely take on the camera’s commemorative arc.

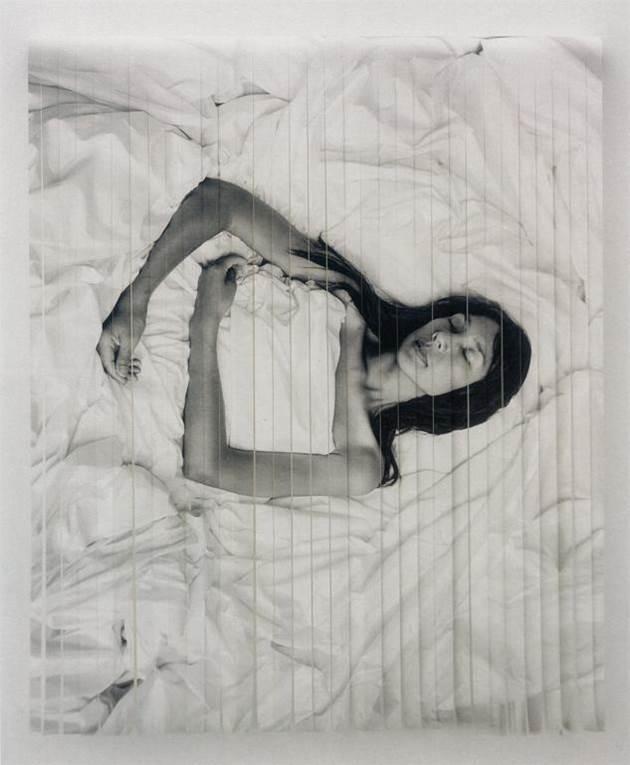

Belmore created the photograph “Fringe” for a billboard in Quebec—the enormous image of the woman’s harmed and mended body set into the skyline. This use of the photograph can fruitfully be compared to Felix Gonzalez Torres’s photograph of an empty bed, ‘Untitled,’ signifying his mourning for his lover and, also, signifying the AIDS deaths of his generation, of which his lover was one and he destined to become another. The billboard showing sleep—as Belmore’s image ‘State of Grace’ shows sleep—reverses public/private discourse in a way that wounds. Suddenly, we are brought into the most private place that holds the body of the wounded. ‘Fringe’ shows the wound as a staged and enormous scar across the back of the recumbent model. The wound comments on clichéd figures of racism—merging Native identity with beadwork and ‘fringe— while also demonstrating the wounds caused by clichés. And yet the sleeping woman, the clean sheets surrounding the bright red wound draw us into a place deeper than social commentary. As with Gonzales Torres’s ‘Untitled’ photograph of an empty bed, in ‘Fringe,’ and ‘State of Grace,’ Belmore draws us into the place of the bed, the recumbent and private space, where she also stages—and the term stages is central to her work—the wounded body signified by highly aesetheticized wounds. ‘Fringe’ features an enormous slashing cut across the back of the model, stitched shut by blood red beads. The stillness and cleanliness of the photograph echoes poignantly the pain the wound causes. Likewise, ‘State of Grace’ is slashed through multiple lines –Belmore has literally cut the image several times—a careful series of slashes that burn through the calm and sanctified image.

The photograph should wound us, if it is powerful, argues Barthes. But Belmore stages the photograph that presents, that stages, deep wounds of historical trauma: the near genocide of Native Americans, and the particular trend of violence against Native women, violence committed largely by men who are not Native. Why does Belmore choose the photograph, as opposed to other media, to stage the wound? Rebecca Belmore is a multi-media artist. The photograph is the proper domain of the aesthetic wound—it marks time, it marks mortal time, it mirrors the mortal body. Belmore’s elegiac images of Native women whom racism has eviscerated, turned into ghosts, fuses the wound with the act of seeing, fuses a kind of visionary truth of history with the aesthetic turn, by taking to the limit the photograph’s connection with the wound, of time, of fate, of the body. These images “Fringe” and “State of Grace” brilliantly call upon the photograph to act as scar, sealing and revealing, in compact visual phrase, a cultural history of violence enacted against the bodies of Native American women.