28 Dec 2014 Modernity and James Nachtwey

James Nachtwey’s Photographs and the problem of the Modern

James Nachtwey’s photographs raise the question of who is responsible for holding trauma, and what is the place of the traumatized in culture? Another way to frame this question is to ask who is responsible for holding in place modernity?

Because the notion of trauma as regressive, a nil-sum, pain without traction, is a benchmark of modernity. In capitalism, we do not learn from suffering; suffering is a sinkhole, a thing to be disavowed, and above all suffering is represented –given film as well as cultural imaginary representation—as the dispossessed ethnic other. The fount of modernity, then, is this division of life from suffering based on the premise that suffering is without benefit—suffering will not bring one closer to the divinity, it will not make one strong, it will not prove one’s worth before the deities, it will not show one the truth of the fleeting world. No, in capitalist discourse suffering is simply what one must disavow and avoid. And so the fountain of the modern is the twin spring of colonialism and capitalism, regimes of disavowal and separation from suffering.

In the not widely viewed film “Silent Tongue” a white, European settler says of Native Americans “They were made for suffering,” thus putting succinctly the economy of the modern: that the one who suffers is to be disavowed and if oneself is suffering, then this pain must be displaced, figuratively, onto the body of the dispossessed colonized subject, whether that colonization be internal or external it is the same psychic paradigm. James Nachtwey’s glossy, beautiful and always elegiac photographs track this disavowed subject of suffering. The question that haunts Nachtwey’s work, as Susie Linfield, writing in The Cruel Radiance, summarizes it, is whether he aestheticizes the suffering of the other. Nachtwey is accused, that is, of making beautiful the other’s suffering. I disagree with this critique, and here’s why:

This question of aestheticization is really beside the point, and misses the point, of Nachtwey’s work. If one approaches Nachtwey’s career from a Foucauldian viewpoint, one would say that we have Nachtwey because he is the expression of our culture. Linfield admits as much when she writes that Nachtwey isn’t the photographer that “we” want but the one we need. But it’s precisely in this coining of a “we” that Linfield gives away the game, indicating that what is really at stake is the creation of a “we” that can, free of harm or danger, watch the other suffer. Nachtwey’s photographs emerge from this crisis but far from reveling in it, his images of severe beauty work as a critique. And also raise the very disturbing possibility that no critique of the modern is ever enough to overturn its press to disavow suffering, that no image will be able to undo the force with which modernity makes of the dispossessed other the place of suffering.

The photograph is of course of the lineage of the modern. And the question of whether and, if whether, how the camera might disrupt the script of the modern is condensed, I think, in the conundrum of Nachtwey’s body of work. That is, he takes the quintessential tool of modernity—the camera that creates instant disembodiment—and uses the camera to critique the way that modernity seeks to separate the subject from the body of pain. In his photographic oeuvre, then, is a compression of the problem of the modern, and a strong argument that, as Bruno Latour argues, we are not post-modern, no, we are only ever deeper into the modern.

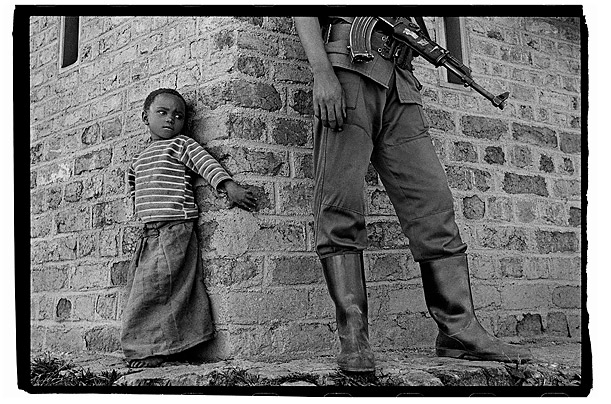

To say that Nachtwey performs the crisis of the modern is to see his work as expiative, and indeed his career has all the trappings of secular sainthood, a legitimate sacrifice of self that should be sounded out in any interpretation of the photographs he produces. The image shown here is from the Congo, and for Nachtwey is a gentle enough image, no overt physical horror on display. And yet this photograph represents the way that he enters the modern and attempts to ravel it—the little girl whose eyes are on level with the photographer’s is creeping against a wall avoiding danger and of course she represents innocence, par excellence, but she also represents the eye versus the gun. That is, her large bright eyes contrast with the soldier’s gun.

The girl’s eyes and the soldier’s gun are the twin foci of the photograph. Her eyes also represent the photographer’s gaze, the delicate gesture of watching, watching carefully, while flattening one’s small body against the wall of the modern, placing oneself at risk to see the corner, is the impetus of Nachtwey’s work. The corner is the limit, just as Kant envisions the sublime, a place where the power of the imagination is forced to enter into the patterns of reason and through that violence revelation occurs: a place of the edge. That is not at all to say that violence itself is a force of revelation, no matter what Walter Benjamin may have claimed for divine violence. Instead, I mean that Nachtwey’s photographs attempt, and sometimes, many times, succeed, in forcing a revelation through the pain of keeping one’s eyes open. Keeping one’s eyes open is the gesture against modernism, for it is the character of the modern to look away. Nachtwey’s photographs, though, insistently stage the gesture of not looking away and, as such, protest the modern condition.

At the corner of modernity, aesthetics is placed. And Nachtwey’s images contend with the crisis of the modern by this crux. The Kantian sublime is only elliptically connected to Edmund Burke’s sublime, connected of course in part by contemporaneity, but also connected by the association of fearsomeness and pleasure. And yet Kant’s sublime is the pleasure of seeing the edges of one’s mind, of retaining, in the place of reason, the dissolutive pleasure of an embodied aesthetic, while Burke’s sublime is the pleasure of seeing danger and harm to others when one knows that oneself is safe. Where are the beautiful and painful photographs of James Nachtwey positioned in terms of these contrary subliminities? Are his war and famine images carriers of the pleasure of Edmund Burke’s sublime, that is, the pleasure of watching the other suffer while knowing that oneself is safe, a pleasure that is not so ethical. Or, on the contrary, are many of Nachtwey’s images exemplary of the pleasure of confronting—of literally approaching— boundaries of knowledge, that is knowing the limits of the possibility of knowing the world, a pleasure like that of Kant’s sublime? That is, do Nachtwey’s violent images of violence bring us to a place of sublime gazing, a limit of seeing such that we step from our harness of easy belief into the dissolution of unknowing that—for Kant—resolves through the strongest aesthetic experience there is—the sublime, the moment of seeing when the cognitive faculties are compelled to physically see, a violent torque that shows us the limits of seeing, and the limits of those categories we establish to comfort ourselves—the truest form of seeing is to be aware that one has not seen, not comprehended. The title of Nachtwey’s dark fin de siècle work, Inferno, indicates a Christian frame, in its invocation of Dante’s Inferno. And yet one can dispose of this Christian frame and still contend with the problem of boundaries in Nachtwey’s work, the problem of the boundaries of wealth, privilege, violence, and poverty in advanced capitalism which is compressed, in many of his photographs, into the metaphor of the pain of seeing, of stretching oneself to see with pain, to “think with pain” visually.

Charlottesville, Virginia

December 2014