28 Sep 2013 Francesca Woodman’s Polka Dots

Francesca Woodman and the Polka Dot Oneiric

The camera-produced image, the photograph, does not invite or permit the viewer’s act of imagination, argues Baudrillard: the hyperreal instead stays above the mortal and dreaming world, a kind of final, fatal Platonic form. Here Baudrillard extends, perhaps, Adorno’s thesis that diabolical popular culture actively deprives the proletariat of the space of dreams, imagination, aesthetic force. Francesca Woodman’s series of almost self-portrait photographs oscillate between popular culture—of a cultic, teen-age girl obsession sort—and fine art—displayed at the Tate, the Guggenheim, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Most attempts to explain the power of her images come up short—either we, who like her work, venerate the cult of the dead girl, deluded in our fondness, or we see her real talent and her links to Surrealism, and maybe her purposive feminism but cannot explain why any of that matters. And yet, I think another way to read Francesca Woodman’s photographs’ power, eccentric but not antithetical to my earlier readings of her work as contending with the Kantian sublime, is by tracing the force of the oneiric as it pulses through the images’ striking constellations of the nude female body, damaged architecture, and frames of violence implicit and obscure. The shapes of things as they emerge in understanding rather than in fact form the visual game of some of Woodman’s best known images

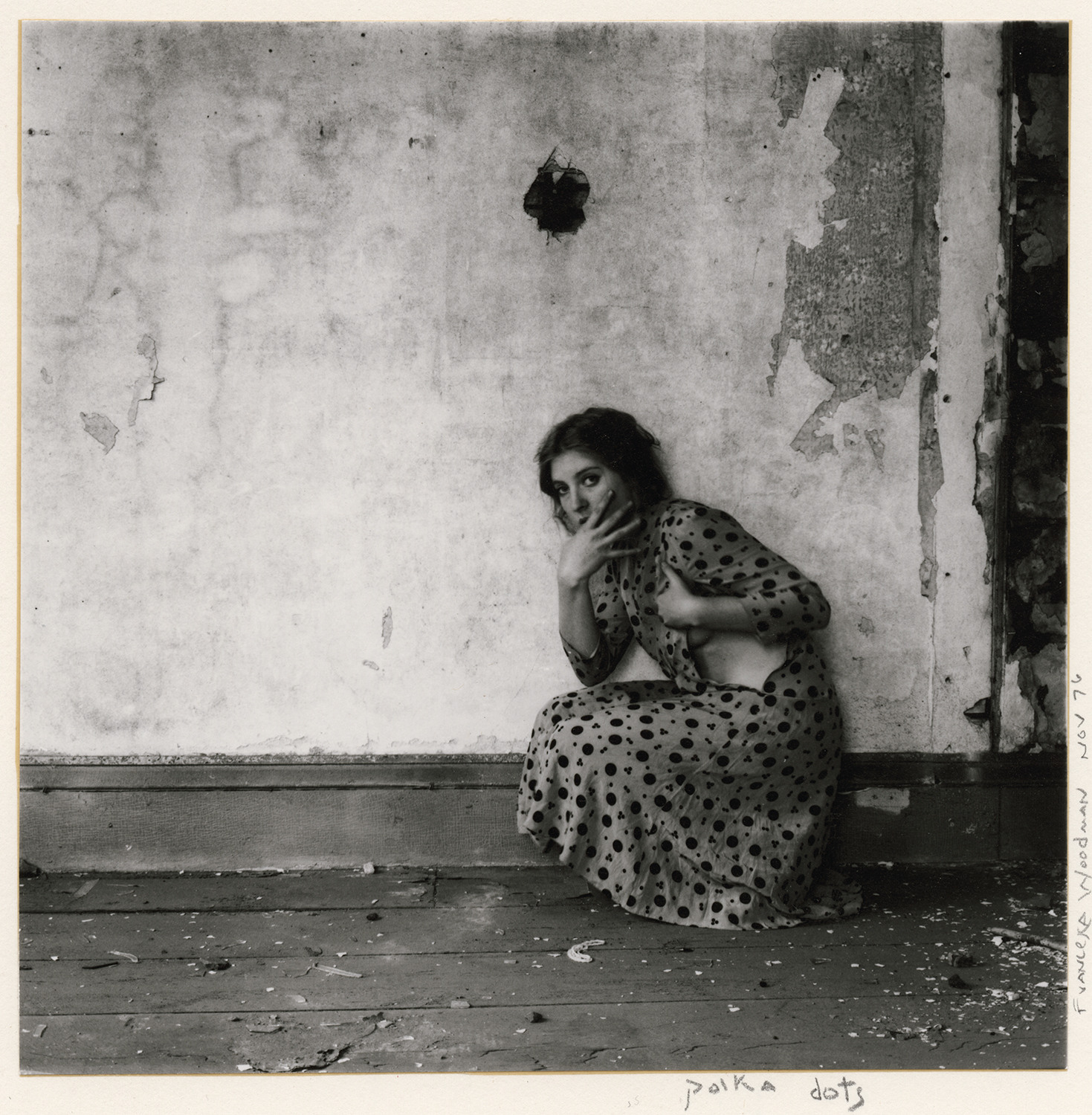

Consider for example this image from Polka Dots. It is one of the two images chosen for the poster of the popular culture film, The Woodmans. The image from Polka Dots pulls the eye to multiple fractionary darknesses in the frame: the polka dots, the damaged walls pitted with dark marks and gaps, the girl’s eyes, and most saliently the girl’s body, which is shown as a shadow beneath and within her partly opened dress. The girl, of course, is Woodman herself. As if she were showing a wound, or the way the body is a site of wounding, as if she were her own doubting Thomas, Woodman places—and invites the viewer to place—a hand in the wound of the open dress, the space of darkness manifest not as the female body but rather as the mortal body overwritten by gendered codes of fragility. The girl in the picture, Woodman, looks not only vulnerable but also terrifying, as if crouched to take flight, her crouched form echoing the large black spot on the wall above her, with its wing-like irregularities.

The image invites us deeper inward, even as the form—the photograph—is the essence of surface, the definitive superficial. As Baudrillard argues, the photograph’s is a realm without depth, or as Woodman herself put it, the photographic image is flattened to fit paper. This play on the premise of depth in the visual scape of superficiality arrests the image, trapped in its own performance, much as dreams are experienced as a concatenation of images and symbols, so compressed, or pressed together, as to impress us with a sense of the impossibility of their complete resolution into translatable meaning. It is this tractive quality of resisting translation that makes some of Woodman’s photographs almost inexplicably powerful. That is, given her social place and subject matter—a privileged child whose subject matter appears to be meditation on the end or edge of childhood’s privilege—we might not expect the images to carry such heft. But they do carry a disturbing and penetrating force: training a gaze looking always into rooms whose inaccessibility manifests as cognate with the limits of language, Woodman’s photographs force their claim to inhabit and sustain an untranslatable visual realm.

But are Woodman’s photographic images evil demons in the Baudrrillardian sense? Maybe or maybe not. Precisely what Woodman’s photographs do not do is negate the imaginary; they propel the imaginary so far forward as to compel our acceptance of the white space around the photograph, that is, compel us to reach and see the end of the photograph. In the same way that Agamben shows that the poem is always about its own ending, so also Woodman’s most accomplished photographs tell us to look away.

In the Polka Dots photograph, Woodman’s thumb is in her mouth, partly a play on infantile regression, but also a literal play on words: the thumb suppressing speech forces us to look to the open dress, with its a sword-shall pierce-your-own-side-also turn of flesh. Language moves from words to code, here, from the words the thumb suppresses in the mouth, to the code of geometrically regressive interiority by which the image stakes its claim. Not an interiority that is manifestly sexual but rather ontological, an interiority of the wound of the eye, the wound of the embodied gaze. The palpable metaphor for the eye here is the polka dots themselves.

The wound that is the eye, the image tells us, grants and is harmed by the force of sight, the room we cannot choose but to inhabit is the room we see. As in dreams we inhabit not the spaces of the demonic but spaces of force when we look at Woodman’s more successful images. While one could of course interpret this “eye” along Bataille’s sexualized terms, I think the challenge in reading Woodman’s photography is that to see the force of the images is to divest oneself of the pathologizing gaze of looking at Woodman as the troubled teen, a bad girl. It is harder but more tallied to the images to see in Woodman’s best photographs the tension of the forms’ harness not of mortal time but fatal space, the body as space in space, a ceaseless and terrifying emergence.

September 28th, 2013