15 Nov 2013 Francesca Woodman’s Zen

Francesca Woodman’s Zen

In Photography Degree Zero, Jay Prosser writes, with clarity and very persuasively, about the Buddhist strand in Barthes’ Camera Lucida, arguing that here, in his last book, Barthes the semiotician confronts or is forced to come up against the limits of words. In particular Prosser emphasizes what he sees as the photograph’s connection to trauma, a connection that Prosser argues is inherent to Barthes’ theory of the photograph as memento mori. This trauma Prosser does not interpret along the lines of contemporary Western trauma theory but instead along the lines of Buddhist notions of the fleeting emptiness of the physical world, the illusion of stability that surrounds those things that occupy time/space.

Francesca Woodman’s House and Angel series of images occupy time/space with a visceral code of trauma. Woodman has been interpreted as putting into photographic images her own trauma. And yet, notably, no one seems to say quite what Woodman’s particular personal trauma might be, other than the eventuation of her act of committing suicide, which needless to say was not an act she had yet completed at the time of making her photographs: it was not a foregone conclusion to the images. My suggestion is that to read Woodman’s images as secret messages of a personal history of trauma is to entirely miss what photography can do. It is not that I don’t think Woodman might have had a personally traumatic history; it is certainly possible that she had a personally traumatic history. And yet that doesn’t matter to her photographs, doesn’t matter when we look at her photographs. Instead, their quality of “thus-goneness” carries the ontological curve of the hollowing spatial real.

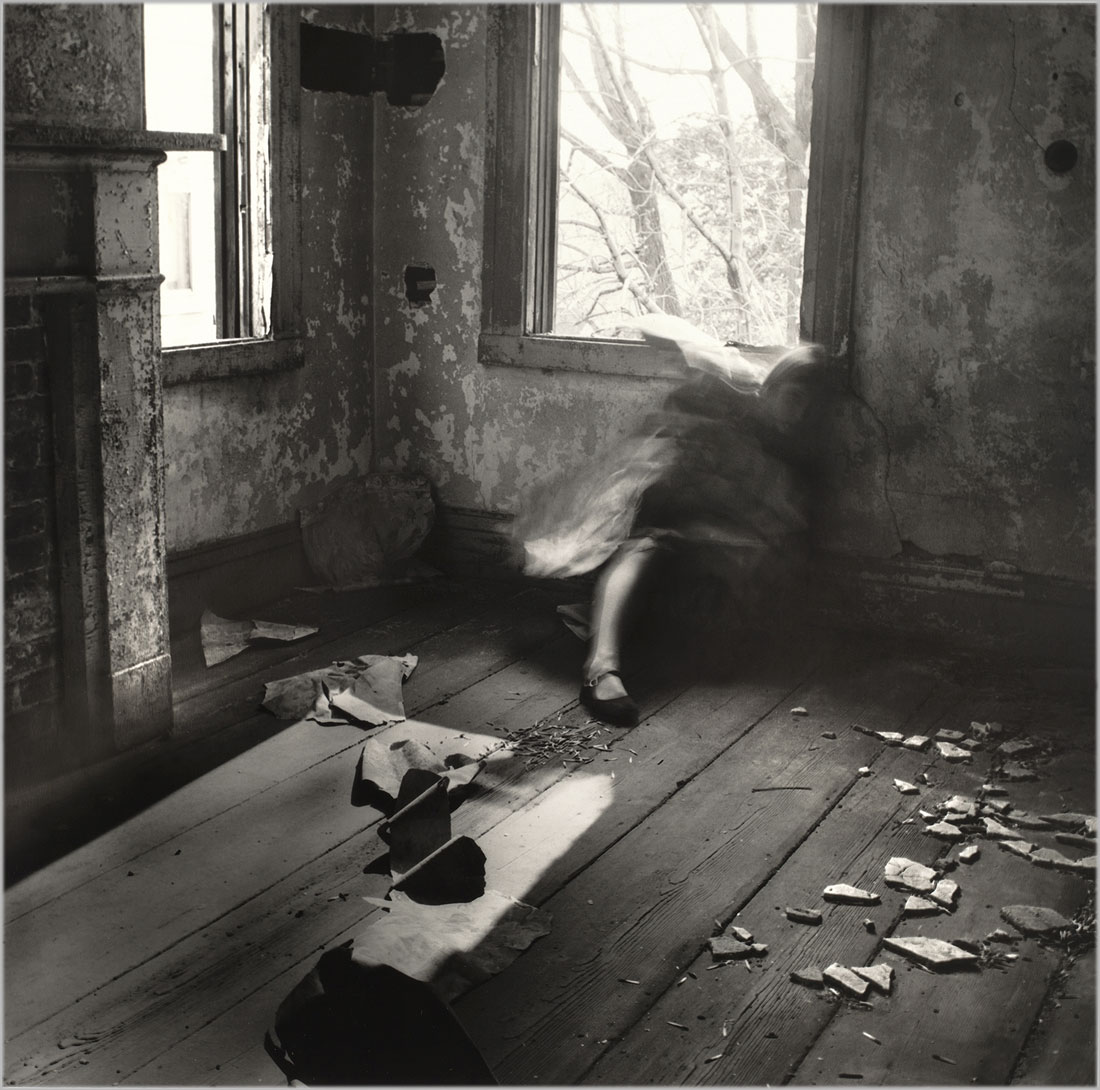

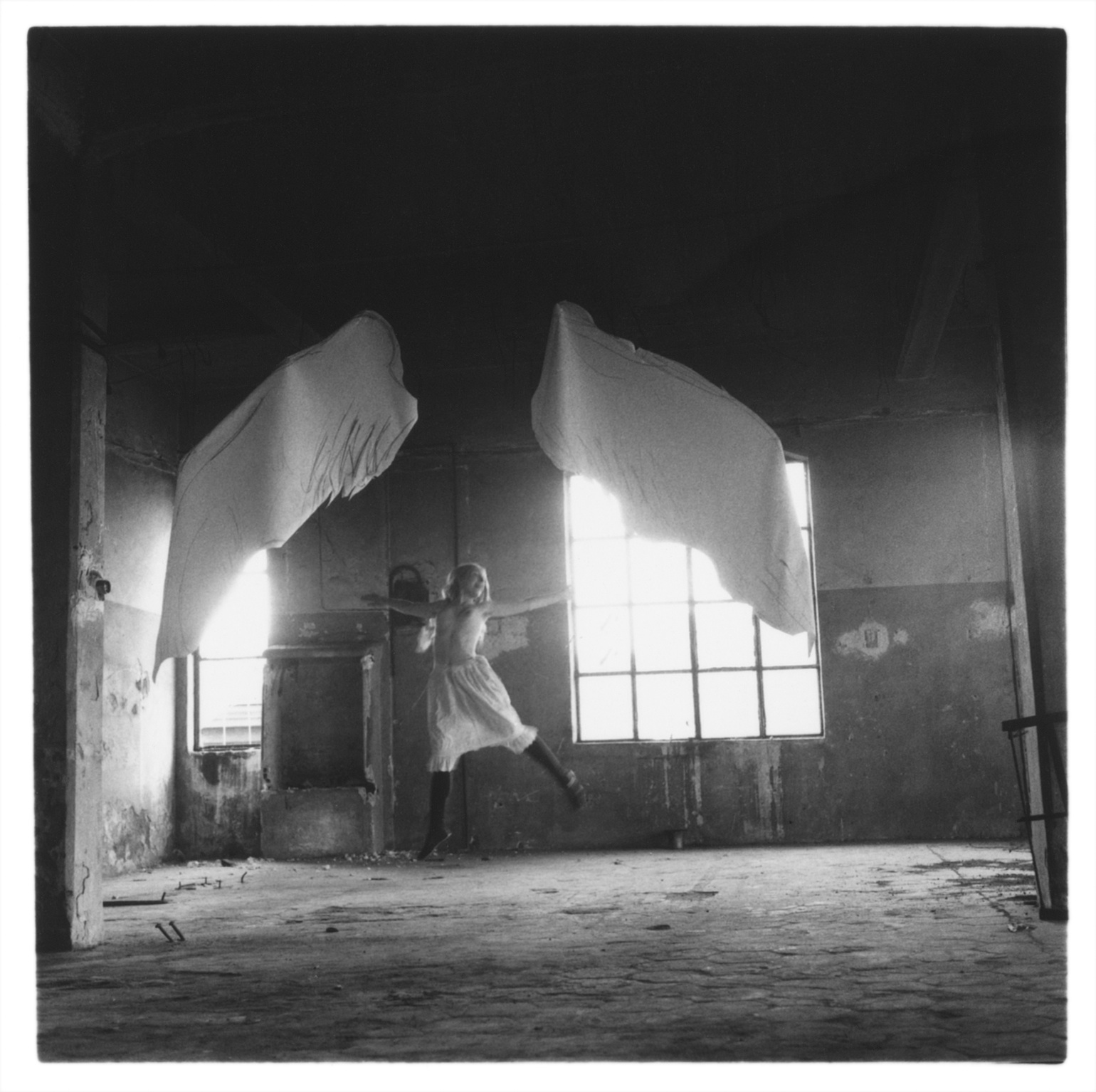

Hollowness and lightness are the codes by which one might read the image above from Woodman’s House series, and this image below from her Angel series.

In both pictures the body of the girl, Woodman, depicts a quality of near disembodiment, with the flourish at the edges of the body as detritus. If Prosser posits the unbearable loss of Barthes’ mother as the engine of Barthes’ need for photography to provide the path of death that words cannot provide, Woodman creates images that provide the path of nullity for reasons that remain powerfully latent in the images. Instead of offering personal confession, the images are deeply informed by the privative code of the photographic as such. As Sloan Rankin has made clear in different commentaries on Woodman’s history: when Woodman was making the photographs on which her reputation now rests she was not depressed but in fact healthy and even joyous. The slant and precarious beauty of the images expresses this delicate space of joy, of the recognition of the emptiness of the physical/temporal world not as a pathological state but as enlightenment. It is not that Woodman was a student of Zen in the sense of studying much less ascribing to Buddhism, but rather that her work exemplifies a careful and serious encounter with the ephemeral contours of embodiment, an encounter that Woodman repeatedly stages in photographs that repeat and exhaust embodiment.

I am fascinated by the gendered aspects of Woodman’s reception history, by the way that meditative intellectual energy is elided as a possible source of her imagery and instead it is supposed that some sort of feminine pathology or the nightmare of the feminine rules her images. Not the nightmare of the feminine but the illusion of objects in time/space is exposed in the delicate and frightening imagery of Woodman’s abandoned House and Angel series. Importantly, photographs taken contemporaneously with these images Woodman organized by titling them Space squared, indicating that the images’ first and second interactions are with space itself, with rendering space in the flat plane of the photograph.

In the House image, shown above, Woodman looks as if she had just crashed through the window, the fractured lines of light seem to emanate from the shoulders of the figure of the girl crouched beneath the windowsill. The blurred figure suggests not only a ghostly figure but more directly a figure without weight, or whose weight is of a different quality and force than we usually interpret as according with the human body. The room seems to sway with a kind of wind, as if the figure of the girl, falling in, shaped the room into a hollow. Each echo of this hollow is articulated and embellished by the photograph’s implicit gestures of counter-comparison: the damaged wall, the fracture line of the wall, the overly bright light (overexposed) light of the trees, the trees as fracture lines, the girl both overexposed and blurred (long exposure time during which Woodman moved), the floor covered with detritus as if the building were emptying itself. This ascesis is Woodman’s enlightenment, her coming to terms with the illusory nature of the physical world by photographing its limits, photographing the places where home is not, in fact, home and cannot protect or sustain us.

Similarly Woodman’s Angel series questions the boundary of flesh and illusion, the unseen seen. In the Angel image from an abandoned factory in Rome, Woodman seems to be trying to levitate, but of course the fey joke of the image is the impossibility of flight for the body in gravity. And yet this picture also abounds with the pun of the illusion of materiality. The present absence of the body as it attempts, comically, to transcend gravity to gain control of its own illusory field. The place where it happens is marked by the photograph as a kind of wound of time, the nubile body half stripped trying to jump out of its skin, or out of its social position or, more straightforwardly, out of its materiality, its illusory secured place in space/time.

The photograph as illusion that leads to truth, what Prosser calls the way of the dead, is particularly relevant to Woodman’s Angel series of images. She creates the most obvious and banal illusion: the image of the angel in a post-lapsarian space, and infuses it with awareness of its falsity that becomes exemplification of its truth. The path of the dead the camera opens through its proscenium function, its function of creating a stage, in Woodman’s Angel photographs. The stage she uses is carefully set and also vacuous, inhabited by a problematic shift of gravity, as the angelic body that tries to lift itself above earth, in the context of an abandoned factory, is marked by the gravity of partial nudity, a partial escape that is echoed by the clumsy wing-like sheets draped above the jumping figure, toward which the figure gestures. The young girl’s partial nudity, her thin arms and long hair, trying to reach the sky signifies in graphic detail the impossibility of flight. But the photograph as the path of the dead signifies its own domain, here, as Woodman stages the facing of the immaterial through the material, stages the invisible through the visible. The angle of the shot forces us to look up through the impossibility of her path, through the narrow gauge of light that is the impossible domain of her trajectory. The photograph becomes the way of the dead not because Woodman has a death wish but because she is true to the medium of photography, to its capacity not to stop time but to show the fractionary gait of time, the mortal divisions of depth that imbricate the body in time that is almost light.